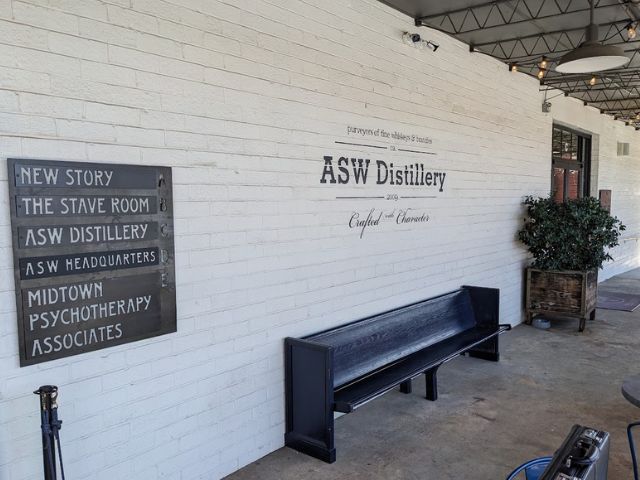

ASW Distillery at American Spirit Works

Distillery Owner? Expand Your Profile

Drew H (00:00:07):

Welcome to Whiskey Lore's Whiskey Flights, the weekly home for discovering great craft distillery experiences around the globe. I'm your travel guide, drew Hanish, the bestselling author of Experiencing Kentucky Bourbon, experiencing Irish Whiskey, and the new book that busts 24 of Whiskey's biggest myths, whiskey lore, volume one. And this is a special edition of this particular episode if you want to hear the travel side of it. I talk a little bit about travel and the Atlanta traffic. I had to deal with getting into talk with Justin Manlet, the head distiller at ASW. I got stuck in traffic for about an hour and actually I had an opportunity to take a little side route. GPS was saying, you could go that way. Well, you could go that way. And I said, well, I'll just stay on the freeway because how bad could it be? Well, it could be that you sit still for 45 minutes and then you crawl for 15 more before you find out that there really wasn't an accident ahead of you at all.

(00:01:07):

So welcome to Atlanta. Anyway, this is something that I haven't done in a while, a extended interview that goes on more than just a few minutes. This thing, we talked for probably about three hours, but we only recorded about an hour and 45 minutes of it. And that is what I'm going to share with you right now. And the reason why I want to share this entire interview with you is because Justin is doing things at a SW that I think you should know about. And he was great to chat with because I could dive into things about scotch and the European way of making whiskey and I could talk about bourbon and the way you're making whiskey in the us and he had experience with doing some versions of all of these. And so I could really dive in deep. We talked about barrels, we talked about tannins, where that flavor comes from.

(00:02:09):

Got some surprises along the way. We talked about Georgia hardwoods, which brought to mind a story from history that I shared with him and surprised him with. And one of the hardest parts about editing this particular episode for the 30 minute version that I put out for everybody else to listen to is that, as you will tell through this conversation, it is just a conversation. We're bouncing things back and forth on each other as we're going through this. So it's not like me posing a question officially take a breath. Here's the next question kind of thing. We're just having a chat and so you're going to get a chance to sit in with us as we go through and talk about many different curiosities I have about whiskey and also learn much more about a SW in the and enjoy this. Okay? And when we get to a part of this where we're talking about red X, that is what you will be soon hearing more about in terms of the whiskey that we are doing a collaboration on. Alright, let's get right into this interview. Enjoy. Here is my conversation with Justin glitz, head distiller at a SW Atlanta. A little bit of an introduction because you've been here from what, 2015 or so?

Justin M (00:03:31):

Yep.

Drew H (00:03:32):

Yes sir. And so how did you get involved with the A SW?

Justin M (00:03:36):

So I started making whiskey the summer after high school, so 2025 years ago, and just my little stills right there. Oh wow. That's my spirit still right there. The copper portuguese still, I can show you my wash still. It's up,

Drew H (00:03:55):

Stored up above. This was your experimental still

Justin M (00:03:59):

Experimental? Sure, let's call it that. I owned a home brew shop, so I started making whiskey or something approximating whiskey in 2000, in actually the attack room of a horse barn on my friend's farm in northeast Georgia. And pretty quickly started making beer after that and actually started making wine with my dad. We would get grapes shipped in. His neighbor was from Italy, so we'd get grapes shipped in from California every year and make hundreds of gallons of wine. So kind of got involved in wine and beer production pretty much right after starting to make liquor. And when I graduated University of Georgia in 2004, our home brew shop had just gone out of business like six months previous normal brew shop where I worked. So I opened home brew shop Originally I went to Terry College of Business to open a distillery. I knew that's what I wanted to do and a friend of mine came back from Iraq. He was a Marine and had some money from his war pay or whatever. And we actually tried to figure out a place to open a distillery, but at the time it was very difficult to open a distillery in Georgia because the state laws that you can only be in a county that has approved liquor cells,

Speaker 3 (00:05:24):

Which

Justin M (00:05:25):

At the time was very few. Now there might be a city or town or municipality or whatever that had approved liquor cells, but the county hadn't and had to be on a countywide. In fact, when I lived in Franklin County before I got involved with Jim and Charlie at a SW, I called the county to see maybe I could put a distillery on my farm there in Franklin County. And an old lady answered the phone and I asked her and she said, there will never be liquor made in Franklin County. It is wet, it is a wet county now it's changed in those 20 years. Georgia has changed immensely in its attitude towards alcohol and alcohol production.

Drew H (00:06:12):

It's really funny to see that evolution too. I saw it in Tennessee when I was doing research on Tennessee's term because it was like the religious factions were not, if it's Baptist, they were not interested in it. And Kentucky's the same because in Kentucky you have the Baptist areas that stay dry and then you have the Catholic areas where all the distilleries are at.

Justin M (00:06:36):

We actually had, this past Thursday, we had a Baptist fundraising organization hosted here in the tasting

Drew H (00:06:44):

Room. That is a change,

Justin M (00:06:45):

Changed a lot. My granny, my granny Ree was Baptist and in Harrelson County, Georgia, and she definitely not having any, so my papapa had been a liquor maker when he was a young man, actually he was more of a hauler. He drove it. He did help at the stills, she made him quit all that and if you tried to talk to him, talked to him about it, she'd hit you with something. And so I kind of heard about it from my uncles. And

Drew H (00:07:16):

So he was kind of like a runner,

Justin M (00:07:17):

A little bit of a runner, hollerer, but also helped. He liked to drink the beer, which is what they used to call mash. So he'd break the cap and drink the beer with a reed, a straw, a reed straw.

Drew H (00:07:33):

So this is the interesting part of moonshining into distilling and really thinking about distillers who start out with an interest in beer and the idea that a lot of distilleries I go to and I taste the beer, and they'll apologize when you taste it because they'll say, okay, this isn't going to taste very good when you go in. Is that something you pay attention to on the front end that you're trying to create a flavorful beer? Or are you creating the beer for the distilling process?

Justin M (00:08:04):

Well, I want to create a flavorful beer, but it's very different from I want to create a flavorful mash or wash. I'd rather use that terminology to separate what I'm saying. So I want to create a very flavorful mash or wash, but it's not going to be palatable in the same way that a beer is consumed. So it's going to have living lactobacilli. So it is going to taste very different. It is fermented much differently, much warmer. So I don't ferment like a brewery would ferment a beer or I would make a beer for consumption as the liquid. I still want it to taste good. I want you to be able to drink it and say, oh, I can appreciate that. But it's definitely not what most people, it's not going to taste like a German pilsner. But yeah, absolutely. You're looking for the malt and yeast derive character in the mash in a similar way as you would beer just differently. So it's going to be, you want it to be more pronounced, in my opinion, in my style of whiskey making, I want it to be more pronounced because I'm separating it. You're not consuming the actual liquid,

(00:09:13):

You're consuming a derivative of the liquid, the distillate. So the more flavorful it is, I want to make a very flavorful spirit, which we will all explain how I do that.

Drew H (00:09:25):

So how did we end up with this still then? Where did this come into the picture?

Justin M (00:09:29):

So like I was saying, my papapa buck, I kind of got, I guess inspired to be interested in whiskey making from stories. And when I opened the home brew shop, I basically, I didn't make a lot of money, but I had all of the ingredients I want out. I realized I was already making all grain beer, whole malt beer without extract or anything. And I realized I was making the basis of single malts, which is what I was drinking at the time. So I just started making single malt whiskeys and if you want to make single malt whiskeys you need, I wanted a still that looked like a single whiskey still. So I had this custom made in Portugal. Oh

Speaker 3 (00:10:13):

Wow,

Justin M (00:10:14):

Okay. In Portugal, a lot of people have their own little stills. It's very common. They're not making whiskey. Mostly they're making something from grapes, grappa, or a lot of times they don't call it grappa, but it's like grappa because they have a lot of home wine making and they'll use the pum, the making of a pumice brandy is what it would be called. I'm sure they have a Portuguese name for it. So yeah, I had that made and imported. I was making all grain beer, let's walk back here, I'll show you my wash still. And I started making all grain whiskey and I was just doing it for myself, just home distilling and learning the process. I had basically free ingredients because I had all the grain and yeast that I wanted at the brew shop and spare time I was young and when I wasn't helping customers, I could be making wash or making beer or making wine or whatever I was doing. So that's my wash still up there, that big stainless one. So I was doing pure, true double distillation pretty much from the beginning. Home distilling has taken off a lot. It's still federally not recognized, but a lot of states have actually said, yeah, that's okay. It's no different than home brewing or home wine making.

Drew H (00:11:27):

I think that changed because there was a federal judge in Texas, I believe it was. So now federally it's open. The question is are the states, so if the states have laws on the books that prohibit it,

Justin M (00:11:41):

It's

Drew H (00:11:41):

Still prohibited in those states.

Justin M (00:11:44):

It's very convoluted. And I don't know what I would do if I was trying to make a decision now whether to do it or not.

Drew H (00:11:51):

It's kind of like cannabis move forward at your own risk.

Justin M (00:11:57):

There wasn't a lot of information on, it wasn't internet information. I just more or less taught myself by trial and error. I threw out a lot of stuff that wasn't good until I figured out exactly how to make it good. And it's a few secret things, things I consider secret. Other people know them

Drew H (00:12:18):

Well. The thing that gets me when you go over to Scotland is that they'll always talk about the shape of the pot still.

Justin M (00:12:24):

But

Drew H (00:12:24):

When you had early distillers that were distilling on just small equipment up in the highlands, they were not necessarily overly concerned with the shape of their

Justin M (00:12:35):

Steel. I think that's a little bit blown out of importance. I mean, it definitely can have an impact on the spirit and certainly certain parts of the wash still certain factors like exactly whether you have a rectifier ball or people call that different things, the reflux ball that's on top of halfway up the head, like on mine, or if you use a worm tub versus a tube, and shell condenser different types of condensers because if the spirit is hot when it is condensing, if it stays hot, it's going to be more volatile and it's going to off gas. Some of the more, usually people call them meaty elements. You can also adjust that with the coldness of your condensate water. Of your cold liquor is what we call it, the water that you're cooling your condenser with. So there's other ways to adjust that too, or whether you use a deflate or that can, there's certainly aspects of still design that can be a big contributor to the whiskey, but the exact shape where they talk about, oh, well this still

Drew H (00:13:40):

Has to have a ding in it has a

Justin M (00:13:41):

Dent right here. Yeah, I'm sorry, that's not true. I don't buy that for a second.

Drew H (00:13:45):

Well, I mean

Justin M (00:13:46):

Not a noticeable difference.

Drew H (00:13:47):

Yeah, if you go to a Glen Morgie, you have the, it's

Justin M (00:13:49):

A great story though.

Drew H (00:13:50):

Well, when you go to Glen Morgie, you have those long swan nets.

Justin M (00:13:54):

What my spirit stills are designed after Glen Ramji.

Drew H (00:13:57):

Okay, okay. So the idea there being that you're going to get a lighter character, it's harder for those oils.

Justin M (00:14:02):

That is absolutely truth. Yeah. Let's walk over there since we're talking about that right now. So no, that's the aspect I'm talking about. That definitely does make a difference. So the shape and the height of the heads, so my spirit still the one on the right there is pattern kind of after a Glen Ji, you are going to get a lighter spirit and more defined cuts on a spirit with a top end that looks like that than you will on my wash stills. More patterned after Glenn Farleys.

Drew H (00:14:35):

Okay. Yeah, absolutely.

Justin M (00:14:36):

So that's going to make, that's pull more character. It's going to make a less a clean spirit and with a wash still, my philosophy is you want everything you want as much as possible. I'm beating the hell out of it in the wash still and trying to get everything.

Speaker 3 (00:14:52):

Yeah,

Justin M (00:14:53):

The spirit still is where I want to be. Have as much fine control as possible. And the line arm, so the swan's neck and the line arm, the part that connects the head to the condenser, that's a big impact too. So if on the wash still here you can see it's angled down. So as soon as the condensate hits the line arm, any reflux, anything that condenses back to liquid is going to run down to the condenser. So that's going to be a more flavorful, what you would maybe call dirtier spirit. It's the wash still, it's only distilled one time, right At that point on my spirit still, that's a horizontal line arm. If you had an ascending line arm that was pointing up, anything that refluxed in the line arm is going to drip back down to the swan's neck into the still to be retiled, so you're getting more reflux. So that is an aspect, absolutely, that makes a big difference in the character of your spirit. But there's other ways you can control that too, how hard you run the steel. There's lots of other things. How warm or cool you condense at, that's just one factor that absolutely does make a difference. Dense, I don't think so, but I'm willing to say, well, maybe

(00:16:14):

I don't know everything

Drew H (00:16:14):

By any means. Fine tune the flavor. You got to imagine that those guys over there are distilling whiskey that's going to, unlike in Atlanta where you're probably going six, eight years, something like that, they're going twice that in terms of their aging. So you don't want to make a mistake that is going to take

Justin M (00:16:32):

You 16 years. Don't want to make a mistake at six or eight years either, lemme tell you. Yeah, that's true. That's very true. Six or eight years is a lot as well. It's expensive. Absolutely 16. 16 is a big deal. Yeah.

Drew H (00:16:42):

Now do you take any cuts? Do you take any of the tails out after your first run or do you take everything that goes through

Justin M (00:16:49):

The wash still is 100%. Everything that comes out of the wash still

Drew H (00:16:53):

Goes into

Justin M (00:16:54):

The spirit, goes into the spirit still along with the faints, which are the portion of the heads and the tails that we keep from the previous batch. And so both stills are running at the same time all the time. So let's start over at the mash cooker. So we call it a mash

Speaker 3 (00:17:11):

Cooker

Justin M (00:17:12):

Because my kind of, it's not innovation. What I do is i'll grain in fermentation and distillation, but with not bourbon generally I do make bourbon on these stills. I make a lot of bourbon on these stills and I do it in that way that it is traditionally done. I make high malt bourbon on these stills actually. So when we're making resurgence, rye malt whiskeys to single malt rides, a hundred percent rye malt or any of our single malts, that's all that the grain is going from the mash cooker into fermentation and into the stills. So it's grain in American style,

Drew H (00:17:51):

Which is unusual. Yes, because very unusual. Most single malts overseas Ireland, I've seen a couple of distilleries that are doing grain in, but almost all of them

Justin M (00:18:02):

Are, right. So in Scotland, and for the most part in Ireland, it's traditionally wash distillation where you're separating the grains and the liquid like you would at a brewery and just fermenting the liquid. So there's some reasons why that is the case. The reasoning that I think was commonly promulgated in Scotland was because the husks have tannins in them over. So you could make too much tannins, you could draw too much tannins into your spirit. I easily prove that was not the case.

Drew H (00:18:34):

The

Justin M (00:18:34):

First four double golds I got from my graining. Fermented. Fermented. Well the

Drew H (00:18:40):

Distilled, the other thing is tradition because they were distilling on fired stills.

Justin M (00:18:45):

Absolutely. So one of the reasons is scorching.

Drew H (00:18:47):

Yes.

Justin M (00:18:48):

So you, well, even before that, it takes up a lot of space in the still. So it's not necessarily efficient. The husk material, corn, wheat, they don't have a husk. Rye doesn't have a husk or not much of one. So it's not taking up as much room. The solid material is not taking as much room in the still with a barley, it has a lot of husk and it does take a lot of room in the still. So that is not super efficient to take up your room in the still with that, you are actually getting some efficiency by leaving that, making a mash with barley instead of a wash because when you lauter it, which is what it's called, when you separate the liquid from the solids like at a brewery or to make wash in Scotland, you're leaving some sugars back inside in the husk material. So usually your efficiency, it used to be about 75 to 80, now they've got different processes and equipment. It's probably more like 80 to 90, but you're still losing some sugar. Whereas mine gets, every bit of the sugar goes into the fermentor and is converted by the yeast,

(00:19:52):

So I don't lose any. So you get a little bit of that efficiency back, not enough to make up for it. But my main reason is for flavor because those solid materials have a ton of flavor. The tannins don't extract because I never strike, which means heat up the mash above 168 degrees. So I don't kill the enzymes in it. It's actually just completely living when it goes into the fermentor. It never gets hot enough to extract tannins anyway until the wash still. And it's not much above that for very long that temperature for very long. Also just don't think tannins actually distill over.

Drew H (00:20:28):

Yeah,

Justin M (00:20:28):

I know they don't.

Drew H (00:20:29):

Now it'd be interesting

Justin M (00:20:30):

Not to fight anyone over it though.

Drew H (00:20:31):

It'd be interesting to see. I don't know if you've seen the mash filters that they're starting to use overseas where they compress as much of that liquid out of there as humanly

Justin M (00:20:40):

Possible. But so the traditional philosophy from winemaking, just to lean into that kind of aspect of my past is if you over compress your pumice when you're making wine, you extract too many tannins and that you are drinking the actual substrate, the actual liquid. And that will, so if you're trying to make a delicate kind of low tannin wine, you don't want to over press.

Speaker 3 (00:21:02):

Yeah.

Justin M (00:21:03):

So I don't know. But then again, they have scientists whose entire job is to do that in Scotland, so I'm sure they've got it right. One last thing I want to say about grain in the main reason that you don't traditionally wouldn't have traditionally done grain in fermentation and distillation with barley is because of scorching. So with a fired still with the actual fire, you always have to stir the still with a bourbon or anything, you always have to stir that liquid till it comes to a boil and then the boil will stir itself.

(00:21:35):

Well, if you don't have something to stir it, that boil, when you have too much solid material in there, the rolling boil is not enough to stir it and it will scorch. So we actually have now machines that stir our whiskey, our mash inside the still and they have that in Scotland, but this kind of goes to the still design. I had these made by Ven to allow me to go back to kind of combine these traditions together. And so when the first distillers came to America, they had the wash tradition. They weren't distilling from a mash, but when they came here and started using American grain and maize primarily, but also rye, those don't actually louder, they don't separate. You just can't do it without centrifuges or something. So they had to make a mash. They had to leave the solids in for fermentation and distillation. They couldn't separate it and their solution was to stir the pot with the cap off until it came to boil. Then you put the cap on, seal it up with the rye paste, and now it's boiling and it stirs itself. And because there's not a ton of husk material in those, it doesn't scorch.

(00:22:48):

So the American tradition, what I do is I just combined that American tradition of mashing with Scottish style distillation. And it's not my innovation because it's exactly what the first distillers in the 17 hundreds, they were using traditional double distillation from Ireland and Scotland, but they were doing grain and fermentation and distillation. So I just went back to that and also apply it to bartley or R malt or wheat malt or whatever I want to do. And so the way I accomplish that is by having ome rather than getting four size stills, which I would love to have, but they don't make steam. They use steam coils usually, and they'll have rummage, well that won't work, that will scorch if you try to put a thick mash of barley in there. I had ven make me the top end of these stills to be Scottish because it does make a huge difference rather than just having a pipe that goes straight up. I do believe that makes a difference. But they made me steam pans. Ven dome took, basically it has a steam jacket just in the bottom

(00:23:59):

To heat the still, which is a gentle way of heating the steel as compared to a coil, which is going to scorch on the coil surface and be a mess. And then it also, I have a giant impeller in here that spins the fool out of that mash so it can not scorch. So anytime if my liquid, as you're distilling your liquid level because you're distilling liquid off of it, it's getting thicker and thicker in the mash still. So for the last 20% of the run, we'll turn the agitator on just to make sure, but we don't generally have scorching issues. Some still makers will make a steam jacket that goes up the side of the

Speaker 3 (00:24:37):

Still

Justin M (00:24:38):

Also not good because now when liquid level drops, you can have heat being applied above the level of the liquid. And so that is not good. So yeah, Vendome has been great to work with and couldn't do what I do without vindo, not my style. So they made these for me to basically do what my philosophy for this distillery was going to be, this whiskey production, which was kind of a different thing than what the vast majority of distilleries in the world do.

Drew H (00:25:10):

So do you still run the stills a little slower or do you feel that because you can now protect against scorching that you can?

Justin M (00:25:18):

No, the more aggressively, like I said, we beat the hell out of it. We run it as fast as we can. That's kind of more determined by how fast we can cool it. We don't want to be running it so fast that it's not cooling, it's coming out too hot,

Speaker 3 (00:25:35):

Right,

Justin M (00:25:35):

The distillate. But we run it pretty hard and take everything and then the spirit still we're running slow the time it takes to run the spirit still. We do two mash distillations in that time and then all of that. So we do, we run a thousand gallons of mash through the wash still every day. And then the low wines from that plus the faints from the day before is running at the same time in the same amount of time through the spirit still. And that's kind of the Scottish method, except a lot of times they'd have a bigger wash deal where they would not have to do it twice.

Drew H (00:26:08):

Yeah. Let's talk about tannin for just a moment because I experienced tannin during a tasting as a bitter note that

Justin M (00:26:16):

Stringency,

Drew H (00:26:17):

Right? A lot of times it gets blamed on the barrel. You talk about it getting from the grain. So

Justin M (00:26:26):

It comes from the barrel. Yeah. So there is tannins in the grain, in the husk material of the grain. Absolutely. And if you make a beer and you accidentally get it way too hot for too long, the grain, not the wort, which is what the portion of the beer once you've separated it from the grain is called. If you get the grain too hot, you will extract some tannins. Now some traditionally the pilsner was invented by boiling decoction, mashing by boiling a portion of the actual mash with the grains in it. That doesn't get too tannic. And there's not many people who do that anymore in America. There were some went back when we cared about really exciting traditional craft beer styles. And there's still some that do that. They still do it in Germany and c Czech Republic and other places in Europe. So you do have tannins in the husk material. It takes a lot of heat and time boiling, right to extract that in a aggressive way. And then you also would have to be distilling that tannin over. And I don't think it distills over. So when you taste a whiskey that has a lot of tannin structure, when it's good in whiskey, I call it tannin structure,

(00:27:45):

When it's too much, I call it as stringent, right as stringent tannin. So enough tannin structure is a good thing. Too much is astringency and that is coming from the barrel. And my best proof of that is that we could, every barrel is different. It just is. Every single barrel is a little different. And you can taste one barrel that is the same batch. I mean we do this all the time, every day. Practically you can taste one barrel that was the same batch of distillate, exact same thing that went from the barreling tank into this barrel. And one will be a little bit more astringent or even a good bit more astringent. That is the barrel.

Drew H (00:28:21):

Okay. The other thing in this process is making the cuts off your spirit still. And so what is it that you are trying to achieve and is it different between when you are running through something that's a corn

Justin M (00:28:36):

Whiskey

Drew H (00:28:37):

Versus a single malt?

Justin M (00:28:39):

Oh, absolutely. So everything I do, you'll notice there's no control panel, there's no computers, everything. I don't like robots. Everything is a valve, a motor starter. It's all hands-on that the way that I make cuts is those valves up there or wit who my friend who I taught to distill, he also makes the whiskey here. We usually do that side by side. So those valves up there is actually what is sending the cuts to a place and it sends them to these via gravity to these tanks down here, low wines, tank hearts or spirit or money tank. And then faints tank here, that's split inside. So we are just using sensory analysis to evaluate the spirit running off the spirit still. And we use our years of experience. So I guess I've been running these stills for nine years, almost 10 years, about nine and a half, something like that. So have an idea of when things are going to be, but then we're using sensory analysis, smell, but also taste to determine whether to make the cut from heads to hearts or hearts to tails.

Drew H (00:29:53):

So when I was at Waterford, it was amazing. We were going through and tasting it different points during the run.

Justin M (00:30:00):

Oh yeah.

Drew H (00:30:01):

And Noel was pointing out how there's a point where you're going from the heads into the hearts. That's a really special area of that run. So the vision I get is that the distiller is over here going, okay, I know it's probably somewhere within this 10 minute window. Are you just over nosing? And so

Justin M (00:30:26):

That kind of depends on the spirit you're making and how you have designed it. And if there's a specific element you want in that spirit, you could miss that very easily going from, for example, a certain fruit quality,

Speaker 4 (00:30:39):

Those

Justin M (00:30:39):

Are esters that are out of hides that tend to come out a lot in the heads, but too much in the heads. So you're trying to get that, the way that I explain it is if you look at a rainbow, right? The colors between a rainbow as you go red, orange, yellower G green, right?

Drew H (00:31:00):

Royal G biv,

Justin M (00:31:00):

Right? Royal G biv, the colors don't go from green to or let's do red to orange. I remember that one red, it doesn't go red to orange with a clean line. It's a gradient

Speaker 3 (00:31:11):

There.

Justin M (00:31:12):

So the cuts are in that gradient. And what we're doing is we're looking, we're tasting sensing in that gradient for what we want from it. So it kind of depends on the spirit you're making and your goal for the spirit. Mine is a little different because part of my design for my whiskey making process here is that, so lemme start by saying this, American distillers say bourbon distillers will say, well, we use grain and fermentation and distillation, and that pulls more flavor from the mash. And that is true Scottish and Irish distillers will say, well, we use pot stills or largely pot still single malt distillers anyway. And that pulls more flavor from the wash. And that is also true. And all I'm doing is combining those two things, right? Okay. When you take mash and you put it in a continuous column still it's not in there for very long. When you take wash in Scotland or Ireland and put it in a pot still it's in there for a long time, but it's just the wash. So what I'm doing is I'm boiling all those solids like you would in a continuous column still for four hours.

(00:32:18):

So I'm pulling a ton of flavor

Speaker 3 (00:32:20):

From

Justin M (00:32:20):

Them, hopefully good flavor, right? So that's my goal is to make really good mash because I'm going to pull all of the flavor from it is going in the low wines and it's going to be a ton of flavor. So what do you do when you have really flavorful low wines? You can take a wide now. So the middle of the heart is your spirit

(00:32:40):

Or not the middle, the kind of, I say the middle of the hearts that's close enough. It's the furthest away from the flavor. A lot of the flavor is concentrated in the heads and the tails, but it's not potable, right? It's not drinkable. So you just take a narrow cut of hearts, you're not going to get as much flavor. It's going to be clean, it's going to age quickly. You're not going to get as much flavor. But if you have a ton of flavor, those hearts have, the more flavor you have, the more all of the hearts have it. So I can take a relatively narrow cut,

(00:33:18):

Not as narrow as you would if you were making a really light spear. And it kind of depends on what I'm making, but I can get a lot of flavor without having to have kind of dirtier aspects of the heads and the tails depending on what I'm making. And then also because we use mostly new barrels because it's America and we mostly have to call it the things to call our whiskey, the things we want to call it, that char in the barrel is going to clean it up extra. So those are all parts of the designs of how I make whiskey here that are a little bit different than most places. But when we're, so take tire fires. A good example. Tire fire is my single malt that's made from a hundred percent heavy peed malts, like 45 ppm. It's a hy, it comes from Inverness. So it's a hylan peat, not Isla style, the flavors, the Creoles, there's tons of different Creoles and they mostly come out, a lot of them come out in the heads. I don't like all of those Creoles. A lot of people love the bandaid flavor. That is not my favorite flavor.

(00:34:21):

I love malts or I love isle malts. I love really Petey whiskey, but not so much the ones that taste like the bad home brews that people were bringing to me at the brew shop. So I make the cuts on that, or Whit makes the cuts on it when he's doing it to not include the Creoles. We don't like,

Speaker 3 (00:34:39):

Okay,

Justin M (00:34:40):

We want the really smoky, and I don't mind some medicinal flavors like iodine or briny. If it's got a chloro septic kind of quality, we're going to put that either down the drain or into the faints tank.

Drew H (00:34:56):

Yeah, I've talked with someone who said they're not a fan of, I like leche as a single malt, but they say it's very crea soap. And so

Justin M (00:35:08):

I like the creosote

Drew H (00:35:09):

Quality. So the question is, is that coming from, what is that coming from

Justin M (00:35:14):

That comes from the peat.

Drew H (00:35:15):

Okay.

Justin M (00:35:15):

Yeah,

Drew H (00:35:17):

It's interesting to hear you talk about that medicinal note being in the grain rather than what I always assumed, which was that it was coming from that iodine in the water down near Isla on that Atlantic

Justin M (00:35:30):

Coast. It's possible that that is absolutely a contributor to it, but I think that's more of a contributor to it as it applies to the peat

(00:35:39):

On Isla, right? So the peat in Isla catches that seawater because it's a terrible, ridiculous place to live and full of storms or whatever. It's making it way to the peat. And then when they use the peat to kill the barley, it's picking up those flavors. So you don't get those flavors in highland peat because it doesn't have those flavors in the peat. I mean we certainly get those flavors in tire fire and a little bit not as much, and it's a small enough amount we can cut that out and not so much the iodine. More you tend to get more of the bandaid quality, which I specifically don't care for.

(00:36:17):

I don't judge someone for liking that I want to make whiskey. That is exactly how I like it generally. Well other than barrels. So like I said, I prefer to use a used barrel if I had 16 years or 20 years, we do mostly new barrels, which I have come to love, new barrels and what they give me. So other than that, I tend to make whiskey. I want to make whiskey that I like. And if I don't like a flavor and whiskey, unless you specifically order me to make something that's going to happen, I'm probably not going to have it in there.

Drew H (00:36:48):

So the fusel oils that come at the end, the conjures tends to work out with the barrel, with the char from the barrel. So when you are making your cuts, are you kind of determining ahead of time how much of that tail you want to leave in because this is going to be a longer aged whiskey versus a shorter aged whiskey.

Justin M (00:37:10):

So I mean, the way that the compounds and the heads and the tails, age usually is a little bit different. So usually the heads just take time to break down and the char can clean them up a little bit. The tails flavors, the congeners and the tails usually break down faster and are more readily kind of, I don't know, converted to nice flavors by the or by oak, the red layer, whichever portion of the barrels doing it. The tails tend to be more, I guess palatable in a shorter period of time. So if you take a really so continuous column still bourbon, you can't remove the heads

Speaker 4 (00:37:58):

From it

Justin M (00:37:59):

Because the heads are continuously flowing through the plate that they're pulling the steam off of the distillate or the condensate boards, distillate. There's a lot of heads in that if you do an analysis of bourbon, it's got a lot of heads, compounds in it, it's going to take char and time to break those down. They do become nice. So the classic one I use is isoamyl acetate that turns into banana flavor. At first it's sovereignty and then it turns into banana flavor, which is not my personal favorite. Some people love it. And then it breaks down into over more time into more what I would consider more flavors than that kind of banana quality. But that does take a charred barrel and it does take some time. So traditionally single malt pot distilled whiskey does not have as much heads compound because you don't want to risk that. It doesn't break down without the char fast enough. And then it's heady in

(00:39:00):

12 years or 10 years or 14 or 16 years, whereas the tails are pretty reliably. They break down fairly quickly. So I'm more comfortable generally with a good many tails in my spirit. You do get a lot of good flavor from tails, especially if you have four to six years, which pretty much everything we put out is well over four years. Most of it's the single malts, resurgences duality there more in the five to seven range right now that we put out. And then the bourbon, our pot still. So we make about 500 barrels a year and we split that between an immense number of products. So you probably know. So we do both sourced whiskey and in-house distilled. And there's not many people, I think distilleries in America that do it to the level that we do it, that take craft this seriously. And this largely 4 5500 barrels a year is nothing to sniff at when it comes to craft whiskey

(00:40:07):

And also are willing to do sourced bourbons. And the fact of the matter is, I can't make a bourbon on these stills that fits the very narrow goalpost that most people have for bourbon. It needs to come from a continuous column still with pretty much similar inputs and corn and grains and it needs to be aged ideally in a certain part of the country to kind of hit those goalposts. So that's what we do. We need to hit those goalposts for people, we hit those goalposts for those people. And we do awesome whiskey as well that we make in house. So we do both here in I think, kind of a unique way. I'd like to think about whether many other people are doing it to that degree, but I think it's a great strength of ours. But I do make bourbon on these distills. I make a double pot distilled high malt bourbon, a good bit of it. So it's about 55% corn and 45% of different malts. It's got barley malt wheat malt rye malt, different things. It's basically like, it's called fiddler soloist. So most of the fiddler line is our source stuff and we're very open about that.

(00:41:13):

And except for Fiddler soloist, and there's been some in the past that weren't, like Fiddler syncopation is a hundred percent corn malt. It's the first single malt bourbon. So with the fiddler soloist, it is double distilled, it is high malt. It is not your goalpost bourbon. But man, we get a lot of people who really love

Drew H (00:41:31):

It. Well, I mean that, I tried recently that I said this changes my mind on the concept that bourbon has such a short flavor profile, it extends out and becomes very interesting. But again, we're talking about a lot of malt in there. So that malt is,

Justin M (00:41:55):

Brings a ton of flavor

Drew H (00:41:56):

Getting, yeah. Talk about the sourced bourbon though. What is your strategy with the sourced bourbon just to have one in-house or to do something special with

Justin M (00:42:08):

It? So originally our strategy was source bourbon. So I'm an old time fiddler, like a pretty good old time fiddler of Appalachian music. And originally Jim and Charlie who were the founders of A SW, and they kind of happened in to buy about a hundred barrels of the MGP weeded, the 45% weeded mash bill. And it was good. It was really good and it was a good deal. And Jim came up with the idea to call it fiddler because I would do things to it. And I was like, well, just to warn y'all, fiddlers and fiddles are not that cool people. I think they're cool, but

Drew H (00:42:48):

It's a story though.

Justin M (00:42:49):

But no, it turns out people do think fis are cool. I didn't know. So I usually do something to it for the vast majority. So our biggest one for years was Fiddler Unison was an actual blending of that MGP wheat high wheat mash bill with the fiddler soloist in different amounts. Kind of like Woodford Reserve, that's nothing innovative. That's what they do. I think we put more of the fiddler soloist in it than they do with the Woodford Reserve, the Laban Graham pot distilled, but can't prove that. So that was a big one for years and I was fiddling with it. I was blending our in-house stuff with the MGP high wheat, and in the end we really wanted to make Fiddler soloist its own major thing and stand on its own. So we had to pull it out of there because we're selling too much of the unison. I could never have Fiddler soloist our in-house pot distill bourbon. I just kept running out of it.

(00:43:53):

So now that is Fiddler weeded and it is me and Whitt designed that one from the ground up. It is still fiddled with some of it is double barreled. And we will continue to always be double barreled. And it's a micro batch. We do four barrels at a time and we match those barrels to each other. So I mean, we're still very deliberate in our construction of that whiskey. Not just the design of it, but how we approach it all the time. And I think it shows, and I think in taste tests at that price point, it really shows

Drew H (00:44:26):

Well, it's one of those whiskeys that I have to, and anybody that's listening to the podcast for a while knows weeded whiskeys for me, unless they've been aged for a long time. I've never really been impressed with the flavor of wheat. But I tried that one and it's like there is flavor going on. A lot of interesting flavors going on in this.

Justin M (00:44:49):

A lot of that is how we blend the barrels across batches. So we can sometimes be a fairly subtle grain, generally considered one of the more subtle grains, but that's what a lot of people like about weeded whiskey of weed, bourbon rather. So what not everybody needs to like every whiskey. And what I try to do is one of the reasons we have 40 different whiskeys

(00:45:17):

Is that I never want someone to say, I don't like any of your whiskeys. If you don't like one of my whiskeys, you just don't like whiskey. I make something for everybody who likes whiskey. And Fiddler weeded hits a huge segment of the consumer base who loves that. And I think it's really good. I drink it myself. Another good example of the fiddler concept is the Georgia Harwood, which that's been, for the most part, it's been different spirit, but me and my dad cut down white oak trees. And so I started this in 2012 when I first started working with Jim and Charlie to build this place. When they made me a partner in the company, we harvested white oak trees and we slab off all the sapwood. So it's just the heartwood and we slab it down and I aged on my farm and then we saw the heartwood down into staves. And then I used to do all this myself. I don't saw it myself. I don't band saw it anymore. I still cut the trees down. I do all that. It's too much for me to ban, saw it all. Now, I never even had a ban saw using circular salt. It's terrible. And I would hand char in an open fire.

Drew H (00:46:33):

Okay.

Justin M (00:46:33):

It was a lot.

Drew H (00:46:34):

Yeah. And I have a story for you after we go through this. Yes.

Justin M (00:46:39):

So that usually that is sourced spirit now, but man, it is a lot more work than anything else.

Speaker 3 (00:46:47):

So

About ASW Distillery at American Spirit Works

Tours available.

Take a Whisky Flight to ASW Distillery at American Spirit Works

Map to Distillery

Note: This distillery information is provided “as is” and is intended for initial research only. Be aware, offerings change without notice and distilleries periodically shut down or suspend services. Always use the distillery’s websites to get the most detailed and up-to-date information. Your due diligence will ensure the smoothest experience possible.